Vamos a comenzar esta parte con la definición de Schmitt de lo político. Como se verá, se trata de un concepto sustancialista asociado al origen de las naciones y a la posibilidad de la guerra. En esta marco, hablaremos del sentido o sinsentido que tendría hablar de una guerra contra la humanidad y, sobre ello, nos referiremos al ‘enemigo absoluto’ desde la distinción entre régimen y Estado. Y esto nos llevará finalmente hacia algunas conclusiones del tipo de la filosofía práctica para los sucesos contemporáneos de la política peruana.

Para comenzar, la definición de Schmitt sobre lo político se basa en el criterio de distinción amigo – enemigo, de la misma forma que la moral requiere de la distinción entre el bien y el mal, y la estética posee el criterio de la distinción entre lo bello y lo feo. Una comparación analógica que no debe significar en ningún caso una equiparación entre lo bueno y el amigo o entre lo malo y el enemigo, de la misma manera que lo bello tampoco puede identificarse ni con lo bueno ni con el amigo. Además, es importante indicar que lo político no se reduce a una identificación con lo estatal, pues en las sociedades democráticas contemporáneas el Estado no tiene el monopolio de lo político sino que ámbitos tales como la religión, la cultura o la economía misma, que son instancias sociales, dejan de ser neutrales y se vuelven potencialmente políticas. Así, el Estado tal y como lo conocemos ya no puede ser considerado como un ámbito distintivo de lo que llamamos precisamente ‘lo político’.

Las razones de un conflicto pueden ser religiosas, culturales o económicas, pero lo que las hace eminentemente políticas es el carácter mismo de conflicto que subyace a la lucha política en cuanto tal. Esto significa que la autonomía de tal criterio no supone necesariamente una independencia en la realidad pero sí supone un diferente modo de ser constitutivo de lo humano. Lo que ocurre es que la manifestación del conflicto en esas otras áreas es sólo la expresión de una naturaleza más originaria del hombre y del Estado. Así, esta concepción esencialista de la política subyace al origen de las naciones cuya naturaleza es entendida desde una perspectiva romántica en tanto que apela a la idea de una especie de sentimientos originarios puros. Desde esta perspectiva es que se afirma que los pueblos se definen en tanto que se agrupan como amigos y por negación de sus enemigos.

Ahora bien, el surgimiento de las nacionalidades y de los Estados – nación es un hecho que, generalmente, tendemos a ubicar en la Reforma Luterana. Sin embargo, el carácter conflictivo de la naturaleza política en su sentido óntico parecería estar inscrito en todo individuo si nos ceñimos a la concepción sustancialista de Schmitt. Por lo tanto, los Estados – nación que conocemos no serían sino una de las últimas expresiones de este concepto de lo político. Estados que, incluso, al ser invadidos por la sociedad civil, como se ha señalado, no suponen ya una identificación simple con el hecho político.

De la misma forma, este carácter esencial de la distinción amigo – enemigo también se puede referir a las diferencias partidarias que se producen en el interior de un Estado. Así, no se entienden como simples discusiones sino que la “lucha partidaria” conlleva necesariamente la idea de “lucha hostil”, entendida ésta como posibilidad eventual siempre presente dada su naturaleza existencial. Por ello, desde esta perspectiva, el nivel máximo de la enemistad encuentra su cumplimiento en la guerra, ya sea como guerra externa o como guerra civil. Esto no hay que entenderlo en el sentido de Clausewitz, para quien la guerra no era sino la continuación de la política por otros medios. Sino que ha de comprenderse en el sentido de que la guerra es el presupuesto de la política en tanto que es una posibilidad real siempre presente a partir de la cual se origina la misma conducta política.

Así, se puede considerar que Schmitt no tiene propiamente un discurso belicista mi militarista pues asume que, incluso, una actuación políticamente correcta en contra de la guerra presupondría la distinción amigo – enemigo. También la neutralidad conlleva la posibilidad de que el Estado neutral pueda aliarse con otro Estado como amigo en contra de otro que considera como enemigo. Esto significa un concepto esencialista de la política pero que no resulta determinante de una realidad concreta sino que permite diversas formas de realización existencial. Aunque la definición de Schmitt de lo político no significa por sí mismo un criterio valorativo, puede permitir pensar de manera valorativa la acción política. Una tal valoración a posteriori no anula la descripción a priori ni viceversa. Tampoco debemos entender el principio sustancial de la relación amistad – enemistad como un principio zoológico a la manera de Hobbes, quien repetía la famosa sentencia homo homini lupus, sino que la determinación existencial sobre quién en concreto es el amigo y quién el enemigo procede invariablemente de la libertad del hombre que le es consustancial. Por lo cual, la sentencia latina antes señalada resulta ser cambiada por la afirmación de que “el hombre es el hombre para el hombre”.

Aunque la definición del enemigo depende del ejercicio de dicha libertad en el marco de las agrupaciones políticas, tal libertad no puede llegar razonablemente al punto en que se pueda pensar en una lucha de la humanidad toda en su conjunto pues, entonces, ¿quién sería el enemigo? Ni siquiera el enemigo deja de ser hombre de modo que no hay aquí ninguna distinción específica”.

Si pensamos en la humanidad como el conjunto de todos los seres humanos es imposible pensar en un enemigo de tal humanidad de forma que toda ella pueda agruparse frente a un enemigo común en el sentido de otra agrupación o pueblo de hombres.

Sería posible pensar en un enemigo de la humanidad en el sentido de alguien que desee exterminar la raza humana por considerarse un ser superior más que humano. Sin embargo, Schmitt podría responder que esta última disquisición no tiene que ver con su criterio teórico en tanto que principio distintivo de carácter óntico, sino que podría explicarse como una retórica política que pretende justificar una guerra apelando a un conjunto de nociones alteradas de la idea propia de humanidad. En ese sentido, también aquellos que actuarían en las guerras posteriores bajo la idea de que están defendiendo tal humanidad, lo que en realidad hacen, por contrapartida, es convertir al enemigo en un ser inhumano por razones morales y proclamar su necesario aniquilamiento. Se trata, en este último caso, de la utilización de un criterio moral en un área distinta de la suya, subsumiendo lo político de tal forma que el enemigo termina siendo degradado a la condición de criminal. Una intromisión de discursos que, en realidad, se podría entender como una manipulación del discurso moral para justificar una agresión de carácter hegemónico o en pro de un imperialismo económico. De esta manera, el concepto de humanidad no sólo se impondría acríticamente eliminando el significado de lo político mismo, sino que, además, se convierte en uno de los tantos conceptos ideológicos antifaz hechos para justificar lo injustificable.

Si pensamos estrictamente en una reducción de lo político a categorías morales tal como lo entiende Schmitt, se ha convertido al enemigo en criminal de guerra. Pero habría que diferenciar si se trata de una ideologización previa (como cuando Bush hablaba de la “libertad infinita”), con lo cual la intromisión de lo moral en lo político resulta ser simplemente tendenciosa e hipócrita; o si se trata de la consecuencia de la violación de los usos de la guerra del Derecho Internacional establecido. Una cosa es un gobierno genocida y otra cosa es una unidad política cuya existencia va más allá de un régimen eventual y pasajero. No era lo mismo combatir a los nazis que luchar contra Alemania ¿o acaso correspondió el holocausto con una forma de ser de la unidad política alemana? Por consiguiente, la criminalización del enemigo no puede significar la criminalización de todo un país o una nación. Una absolutización del concepto de enemigo que sí ha ocurrido en la retórica del caso de Irak con la estigmatización del Islam y, en consecuencia, con la criminalización de tal religión.

Por otro lado, en la obra El concepto de lo político, redactada en el período de entreguerras, se criticaba a la liga existente en aquellos años por confundir lo interestatal con lo internacional. El primero de estos conceptos se refiere a la garantía del status quo de las fronteras nacionales por parte de la Liga. Pero el concepto de internacional, como en el caso de la Internacional Socialista, supone una sociedad universal despolitizada al responder a la tendencia imprecisa de buscar el Estado único como un postulado ideal. Para Schmitt queda claro que sólo un Estado ideal apolítico, es capaz de dar tal paso y convertir el enemigo en un criminal.

Sin embargo, tal Estado es para Schmitt una imposibilidad práctica, aunque se preconice teóricamente. Las tendencias hacia esta situación vienen del lado de un liberalismo individualista que, buscando eliminar todo lo que puede coaccionar su libertad (incluyendo el propio Estado y su correspondiente monopolio organizado de la violencia legítima), termina por entronizar el imperio de lo económico y poniendo el aspecto ético – espiritual en la dinámica de una eterna discusión. Precisamente por el lado de lo económico es que tal Estado único resulta ser tan sólo una ficción pues lo que ocurre, en realidad, es que la economía se vuelve en un hecho político al desarrollar nuevos tipos de oposición que llevarían claramente a la guerra, aunque ésta no deba ser entendida necesariamente en el sentido de la lucha de clases marxista. Lo mismo ocurre bajo la idea de declarar una “guerra contra la guerra”, pues ello haría dividir la humanidad entre dos agrupaciones políticas y el criterio amigo – enemigo seguiría siendo la distinción específica de lo político. Ningún autoproclamado Estado universal podría anular lo que es una naturaleza de carácter óntico. Sólo podrá haber el intento de una agrupación de países de apropiarse del derecho a la guerra estructurando el Derecho Internacional bajo sus propios intereses. Así se entiende a la ley positiva como la búsqueda de la legitimación de una situación en la que los interesados sólo pretenderían encontrar estabilidad para su ventaja económica y poder político aunque lo disfracen de discursos moralistas.

Para Schmitt, a pesar de la voluntad de los juristas internacionales de que esto no sea así, ningún sistema de leyes puede evitar la diferenciación sustancial entre enemigos que presupone la guerra. Esto no significa que no se deba trabajar en beneficio de un nuevo orden que establezca “nuevas líneas de amistad” entre los pueblos, al margen de la eficacia o ineficacia de la actual ONU. Para Schmitt, el error está en que el organismo surgido de la Segunda Guerra Mundial fue una construcción de los vencedores que creyeron que su victoria era la victoria definitiva y ello los incapacitaba para poder plantear nuevas respuestas a los Challenges de la historia. ¿No son los sucesos contemporáneos, además de un nuevo Challenge, una nueva llamada de atención sobre la futilidad de un modelo liberal de carácter monista? Schmitt vislumbró que el orden futuro del mundo se convertiría en un pluralismo multipolar y que, aquello que marcará el desarrollo de los grandes espacios, dependerá de la fuerza en que una agrupación de pueblos o de naciones puede mantener el proceso de desarrollo industrial siendo fieles a sí mismos y no sacrificando su identidad por el carácter tecnológico de dicho desarrollo, “no solamente por la técnica, sino también por la sustancia espiritual de los hombres que colaboraron en su desarrollo, por su religión y su raza, su cultura e idioma y por la fuerza viviente de su herencia nacional”.

En otras palabras, que el orden del globo dependerá de un comunitarismo amplio de mundos de la vida fuertes ante toda racionalización sistémica dominante de la techne y el progreso.

Ahora bien, las consecuencias de esta reflexión para la comprensión de los sucesos políticos contemporáneos que nos impelen directamente deberían ser más que evidentes. Tanto si hablamos de los sucesos de Bagua, como de la situación del VRAE o de las relaciones entre el Perú y los demás Estados en los momentos de una aparente carrera armamentista. Una vez que el Estado peruano ha sido invadido por la Sociedad Civil, se pierde paulatinamente el principio del monopolio de la violencia. ONGs, movimientos políticos de naturaleza anarquista con características delictivas, así como partidos de carácter revanchista que estigmatizan al Estado colaboran para la destrucción de cualquier tipo de unidad sustancial o espiritual nacional que debería personalizar nuestro sistema político. Así se termina haciéndole el juego al liberalismo económico y político internacional cuyo resultado no puede ser otro que la crisis mundial.

El ideal de nuestro Estado ha de ser que las formas políticas expresen nuestra herencia cultural y ello no parece haber ocurrido precisamente a lo largo de nuestra república en todo sentido. El desprecio por comunidades andinas o del oriente peruano de parte de un régimen que, por ejemplo, se dedica principalmente a Tratados de Libre Comercio, significa, a la larga, una destrucción física y moral que justificaría una lucha constante contra este sistema. Ello, por supuesto con las salvedades apropiadas: no se justifica ninguna intervención extranjera ni tampoco el terrorismo indiscriminado porque eso precisamente destruye las comunidades que pretendemos defender.

Por otra parte, así como las Convenciones por sí solas no son suficientes para evaluar la justicia en la Guerra, la terquedad en aferrarse a leyes positivas es una ingenuidad jurídica, además de ser un abandono de las experiencias humanas morales que están a la base de cualquier sistema de Derecho. Las relaciones entre personas son más primigenias que las relaciones jurídicas y esto es algo que se ha olvidado tanto en el ámbito internacional como en el ámbito de nuestro país. Asimismo las políticas de la amistad no pueden ser tan ingenuas como para creer que no va a haber conflicto porque nos sometemos a los Tratados

Es en esta línea en que se debe plantear la cuestión de los Derechos. Tan malo es una imposición jurídica de Derechos entendidos en sentido liberal moderno a la manera norteamericana, como el desprecio por la vida y la libertad. Así, la defensa de la comunidad debe verse como defensa de la riqueza cultural, alimentada por la naturaleza material propia. Ni la salvaguarda de un modelo liberal ni la repetición de rebeliones de países vecinos resulta auténtica.

Bagua, el VRAE o lo que se venga en las relaciones internacionales es y será precisamente el resultado de este conflicto irresoluble sintéticamente entre la globalización y la defensa de la comunidad. Así, hemos asistido, y probablemente seguiremos asistiendo, a conflictos sociales con el peligro de que devengan en cosas mayores; y todo es y será el resultado tanto del eterno y dinosáurico paternalismo económico que, no solo está fuera de nuestras fronteras, sino que está dentro y que, incluso, nos gobierna, así como de la marginación y el caos burocrático. Razón que nos lleva a repetir una vez más, junto con las encíclicas sociales de la Iglesia Católica que “No habrá paz sin una verdadera justicia social”.

Last February, by way of an introduction, I put up a

Last February, by way of an introduction, I put up a

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Die State University of New York Press hat die englische Übersetzung des „portugiesischen Tagebuchs“ (Jurnalul portughez) von Mircea Eliade – er war von 1941-45 rumänischer Botschafter in Lissabon – veröffentlicht:

Die State University of New York Press hat die englische Übersetzung des „portugiesischen Tagebuchs“ (Jurnalul portughez) von Mircea Eliade – er war von 1941-45 rumänischer Botschafter in Lissabon – veröffentlicht: Evola hat 1942 „Il filosofo mascherato“, die Besprechung eines Buches von Maxime Leroy über Descartes’ deviantes Rosenkreuzertum und seine Rolle im Rahmen der Gegeninitiation, in „La Vita Italiana“ veröffentlicht. (Deutsche Übersetzung: Der Philosoph mit der Maske, in: Kshatriya-Rundbrief, Nr. 7, 2000) Schmitts „Leviathan“ besprach Evola bereits 1938 in „La Vita Italiana“ (nachgedruckt in zwei weiteren wichtigen italienischen Zeitschriften). Evola kommt im übrigen in Eliades Tagebuch laut Index nicht vor.

Evola hat 1942 „Il filosofo mascherato“, die Besprechung eines Buches von Maxime Leroy über Descartes’ deviantes Rosenkreuzertum und seine Rolle im Rahmen der Gegeninitiation, in „La Vita Italiana“ veröffentlicht. (Deutsche Übersetzung: Der Philosoph mit der Maske, in: Kshatriya-Rundbrief, Nr. 7, 2000) Schmitts „Leviathan“ besprach Evola bereits 1938 in „La Vita Italiana“ (nachgedruckt in zwei weiteren wichtigen italienischen Zeitschriften). Evola kommt im übrigen in Eliades Tagebuch laut Index nicht vor.  A recent study points to

A recent study points to  Documents which have circulated in connection with the Fay/Jones and Taguba Reports made clear that following the issuance of high-level legal advice outside normal Department of Defense channels, command authorities in Iraq no longer considered the Geneva Conventions to restrain them in their handling of detainees. Internal email traffic among military intelligence units is consistent: Once you label the insurgent detainees as “terrorists,” “they have no rights, Geneva or otherwise.” It seems highly improbable that officers carefully trained in the Geneva rules would suddenly discard them on their own initiative. To the contrary, it is reasonably clear that instructions to that effect were transmitted from a very high source. The Yoo memoranda are critical to understanding what happened, and the March 14, 2003 combined with the initial OLC advice concerning treatment of insurgents in Iraq are likely the most significant pieces of the puzzle not yet in place.

Documents which have circulated in connection with the Fay/Jones and Taguba Reports made clear that following the issuance of high-level legal advice outside normal Department of Defense channels, command authorities in Iraq no longer considered the Geneva Conventions to restrain them in their handling of detainees. Internal email traffic among military intelligence units is consistent: Once you label the insurgent detainees as “terrorists,” “they have no rights, Geneva or otherwise.” It seems highly improbable that officers carefully trained in the Geneva rules would suddenly discard them on their own initiative. To the contrary, it is reasonably clear that instructions to that effect were transmitted from a very high source. The Yoo memoranda are critical to understanding what happened, and the March 14, 2003 combined with the initial OLC advice concerning treatment of insurgents in Iraq are likely the most significant pieces of the puzzle not yet in place. Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre).

Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre).

Nel libro Terra e Mare (1) il grande giurista e teorico dello Stato Carl Schmitt interpreta la storia del mondo alla luce della centralità dello scontro geostrategico tra l’elemento tellurico e l’elemento marino, dai quali discendono due diverse concezioni della politica, del diritto e della civiltà. Lo scontro tra questi due elementi ha origine con la storia dell’uomo, basti pensare alla rivalità tra Roma e Cartagine, ma è solo con l’avvento della modernità che l’elemento marino, fino ad allora sottomesso a quello tellurico sembra essere in grado di fronteggiarlo alla pari e anche di avere la meglio su di esso.

Nel libro Terra e Mare (1) il grande giurista e teorico dello Stato Carl Schmitt interpreta la storia del mondo alla luce della centralità dello scontro geostrategico tra l’elemento tellurico e l’elemento marino, dai quali discendono due diverse concezioni della politica, del diritto e della civiltà. Lo scontro tra questi due elementi ha origine con la storia dell’uomo, basti pensare alla rivalità tra Roma e Cartagine, ma è solo con l’avvento della modernità che l’elemento marino, fino ad allora sottomesso a quello tellurico sembra essere in grado di fronteggiarlo alla pari e anche di avere la meglio su di esso.

Come sappiamo, dalla dissoluzione dell’ordinamento medioevale sorse lo Stato territoriale accentrato e delimitato. In questa nuova concezione della territorialità – caratterizzata dal principio di sovranità – l’idea di Stato superò sia il carattere non esclusivo dell’ordinamento spaziale medioevale, sia la parcellizzazione del principio di autorità (1).

Come sappiamo, dalla dissoluzione dell’ordinamento medioevale sorse lo Stato territoriale accentrato e delimitato. In questa nuova concezione della territorialità – caratterizzata dal principio di sovranità – l’idea di Stato superò sia il carattere non esclusivo dell’ordinamento spaziale medioevale, sia la parcellizzazione del principio di autorità (1).

A l'âge de six ans, Günter Maschke, natif d'Erfurt en Thuringe, s'installe dans la ville épiscopale de Trêves, en Rhénanie-Palatinat. En 1960, il adhère à la Deutsche Friedensunion

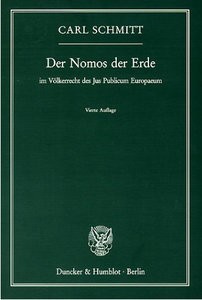

A l'âge de six ans, Günter Maschke, natif d'Erfurt en Thuringe, s'installe dans la ville épiscopale de Trêves, en Rhénanie-Palatinat. En 1960, il adhère à la Deutsche Friedensunion Man möchte meinen, Carl Schmitt ist als Autor heute weniger wegen seiner Liaison mit dem Nationalsozialismus als wegen der Klarheit seiner Schriften unbeliebt. Seine unermüdliche juristische und philosophische Grundlagenarbeit, mit einem kühlen Kopf den Wörtern ihren Sinn zurückzugeben, hat sich in ein reichhaltiges Reservoir deutscher Denkkraft verwandelt. Dies erhellt dem Nachdenkenden die Struktur der modernen politischen Ideologien, sofern sie mit Begriffen wie Demokratie, Parlamentarismus, Diktatur, Souveränität, Menschheit hantieren. Der Begriff des Politischen und Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus sind nun bei Duncker & Humblot in neuer Auflage erschienen.

Man möchte meinen, Carl Schmitt ist als Autor heute weniger wegen seiner Liaison mit dem Nationalsozialismus als wegen der Klarheit seiner Schriften unbeliebt. Seine unermüdliche juristische und philosophische Grundlagenarbeit, mit einem kühlen Kopf den Wörtern ihren Sinn zurückzugeben, hat sich in ein reichhaltiges Reservoir deutscher Denkkraft verwandelt. Dies erhellt dem Nachdenkenden die Struktur der modernen politischen Ideologien, sofern sie mit Begriffen wie Demokratie, Parlamentarismus, Diktatur, Souveränität, Menschheit hantieren. Der Begriff des Politischen und Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus sind nun bei Duncker & Humblot in neuer Auflage erschienen. An interest in Carl Schmitt

An interest in Carl Schmitt Hoy se cumplen 25 años de la muerte de Carl Schmitt. ¿Qué se puede decir sobre el interés por Schmitt a 25 años de su muerte? Compartimos algunas reflexiones “prácticas” para un “buen” uso de la obra del jurista, de manera que siga resistiendo al tiempo como lo ha hecho hasta ahora.

Hoy se cumplen 25 años de la muerte de Carl Schmitt. ¿Qué se puede decir sobre el interés por Schmitt a 25 años de su muerte? Compartimos algunas reflexiones “prácticas” para un “buen” uso de la obra del jurista, de manera que siga resistiendo al tiempo como lo ha hecho hasta ahora.

La Vita nuova (1292-1293) de Dante es el canto que prepara a la recta lectura de la Divina commedia. El lector atento sabe que el ejercicio necesario para la compresión del Amor dantesco en términos impersonales y político-religiosos, depende del soneto de la Vita nuova. Se trata, en este breve libro, de la compresión del dogma del Milagro como evento del Automaton (la casualidad), como la realización del evento excepcional en el accidente. En Dante el Automaton es la inmediatez ineluctable y subitánea del advenimiento en su Ahora perpetuo bajo la forma del saluto. Il saluto (saludo) irrumpe en el tiempo (lo crea más precisamente) para imponer su Salud: Beatrice (1). Se trata, en otras palabras, del advenimiento de un nuevo orden bajo la forma del acontecimiento fortuito: se trata del orden necesario

La Vita nuova (1292-1293) de Dante es el canto que prepara a la recta lectura de la Divina commedia. El lector atento sabe que el ejercicio necesario para la compresión del Amor dantesco en términos impersonales y político-religiosos, depende del soneto de la Vita nuova. Se trata, en este breve libro, de la compresión del dogma del Milagro como evento del Automaton (la casualidad), como la realización del evento excepcional en el accidente. En Dante el Automaton es la inmediatez ineluctable y subitánea del advenimiento en su Ahora perpetuo bajo la forma del saluto. Il saluto (saludo) irrumpe en el tiempo (lo crea más precisamente) para imponer su Salud: Beatrice (1). Se trata, en otras palabras, del advenimiento de un nuevo orden bajo la forma del acontecimiento fortuito: se trata del orden necesario

Voor wie professor Tommissen niet zou kennen, hij gaat de wereld rond als dé Carl Schmitt-kenner bij uitstek, die gans Europa ons trouwens benijdt. Derhalve kunnen we niet om de vaststelling heen dat zowat elke grote natie zijn Schmitt-renaissance heeft gekend, met uitzondering van dit dwergenlandje België. Terwijl juist hier…inderdaad!

Voor wie professor Tommissen niet zou kennen, hij gaat de wereld rond als dé Carl Schmitt-kenner bij uitstek, die gans Europa ons trouwens benijdt. Derhalve kunnen we niet om de vaststelling heen dat zowat elke grote natie zijn Schmitt-renaissance heeft gekend, met uitzondering van dit dwergenlandje België. Terwijl juist hier…inderdaad!

Keith Preston

Keith Preston is the chief editor of AttacktheSystem.com and holds graduate degrees in history and sociology. He was awarded the 2008 Chris R. Tame Memorial Prize by the United Kingdom's Libertarian Alliance for his essay, "Free Enterprise: The Antidote to Corporate Plutocracy."